LEE Yun Bok

2008年6月30日(Mon) 〜 7月12日(Sat) a.m.11:00〜p.m.6:30 日曜休廊

GALLERY TSUBAKI ギャラリー椿

| リー・ユンボク

展

LEE Yun Bok 2008年6月30日(Mon) 〜 7月12日(Sat) a.m.11:00〜p.m.6:30 日曜休廊 |

||

| Lee Yunbok |

今回私が展示する作品は2005年から2008年までに作った作品である。 私の作品は作っている過程で進化する。決まっているのは体を使って考える事である。体と頭を働かせないと何も見えてこない。また、作品はおのずと作り手の人生を投影するものだと私は信じているので、自分もしっかりと日々を生きていきたい。 作業場に入ると緊張が始まる。意図的にも緊張感を持って作業をする。安全のためでもあるし、作品に私のエネルギーを注入する事でもある。作業のために使う道具や機械が自分の一部にならないと表現がうまくできない。作る事に集中している時、緊張感は続き、それが作品の中にも反映される事になる。私にとって作品というものは体と精神で作るものである。私の作品は最初から完全に思い通りにできるものではない。変容していくものである。 作業過程の中で偶然性は作品の重要な要素であり作品の一部である。偶然性はステンレス板をハンマーで叩いて溶接する過程の中で、意図的な形とそうではない形となって現れる。最初に描いたものは過程の中で変わっていくし、完成するまでやり直しながら作る。平面のステンレス板を立体に変えるために物理的な労働力を使っている。作品は単純な形に見えるのだが、作業の過程を見るとそこには強迫的な労働と思惟とが時間に込めてある。肉体を使って成形し、溶接して研磨する。最後に、鏡のようになるまで仕上げていく。面白いのはこの労働の過程を続けていくと、その痕跡が作品から感じないようになることだ。 作品は精神と肉体の限界の境界で作られたものである。体の痛みを感じながら寝て、そして起きる。ハンマーと機械の音と振動、溶接の光、毎日越えていく。私には作業の過程も作品の一部である。 意図的な形で作品を作ると、思考も作品もその形だけに巻き込まれて逃れることができない。作品に込めてあるのは一つの意味だけではない、簡単に言えない「自分」というものが入っている。思考も作品ももっと広がって自由に飛びたい。自分の中から自然に出る形を眺めながら逆に考える。今までとは違う方向から見るための方法である。作品を作りながら今の自分を見る。そこからいろんなものに広がって行く。これが私の原点というものである。 近の作品はドローイングもせずに作り始める。作品を作っていく過程の中で心の動きを聞く。空間をキャンバスとして自由に手で形を描き、両手を合わせてかたまりを作ってみる。納得できる形が出てくるまで反復する。何が出るかはまったくわからない中で楽しんでいる。それでも無意識の中から自然に出てくる形は、今までのそれとまったく違うものにはならない。 作品は人体の一部であるし自然の生命体でもある。または決まっていないエネルギーである。一つ一つ合わせて有機的形になっていく。作品は進化の過程を続けていく。 |

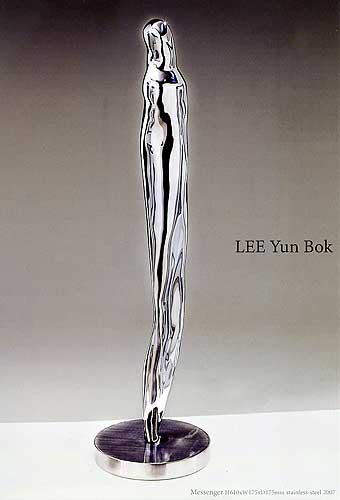

Messenger H610xW175xD175mm stainless-steel 2007

| 魂のかたち――リー・ユンボクの近作について |

| 本江邦夫 |

| ウィル・スミス主演の映画「アイ・アム・レジェンド」は疫病で封鎖されたニューヨークに一人残り、夜ともなれば、いまや凶暴なゾンビと化した旧住民たちと暗闘をくりひろげる医師の物語である。それだけでもずいぶんと怖い話だが、このほとんど荒唐無稽な映画でまさに戦慄が走るのはそうした活劇の場面ではない。静謐な午後、誰もいない店内で主人公が生き人形のようなマネキンに話しかける場面があり、それが今にも口をききそうで、なんともいえず不気味なのだ。そして同じ空間のなかにいる、人の似姿がなぜかくも不安をかきたてるのか理由が分からず、途方に暮れるのである。 たぶん、そこで私たちはいきなり魂の問題に直面したのだ。この精巧な人形に(ふとピグマリオンを想う)魂が入れば生身の美女なのになどと不謹慎なことを頭のどこかで考えたのだ。しかし、魂とは何か?どこにあるのか?これについては誰も分からない。分かるのは、私たちの魂は私たちに寄り添い、ほとんど一体となっていて、顔や背中と同様、直視しえないものということだ。木や石の塊に魂が宿るわけではない。ならば、どうやって魂を、行方の知れない、それゆえに不意に出来するしかないそれをとらえるのか。ここにリー・ユンボクの仕事の意味があるように、少なくとも私には思える。 リー・ユンボクの制作に魂のある種の造形を見るのは、実は今回が初めてではない。何年か前に、双ギャラリーで有機的なフォルムのオブジェを金属板の帯で締めつけたような作品を見たとき、なぜか封印された魂をそこに感じたことがあったのだ。それと比べると近作では魂は自立し、はるかに自足している。しかし、ステンレスの板を叩き上げ空虚を内包した、きらきらしたそれは魂そのものではなく、あくまでもそのかたちでしかないのだ。しかも、ここで本質的なのは老子にいう「有之以爲利、無之以爲用」(有の以て利を為すは、無の以て用を為せばなり)、つまり有(存在するもの)が役立つのは無(空虚)のおかげである、という事態であることを忘れてはならない。 ところで、魂がいくら寄り添うものだからといって、そんなに簡単に姿を見せるわけではない。だからこそ、リー・ユンボクは言うのだ。「作品は精神と肉体の限界の境界で作られたものである。体の痛みを感じながら寝て、そして起きる。(…)私には作業の過程も作品の一部である」と(「覚書」)。自分の分身もしくは他者ともいうべき作品との絶えざる対話、葛藤に魂は付き従い、ほとんど無なるものとして素材に作用する。作者によって「偶然」と名づけられた、これら密やかな出来事の集積ないし総体こそは魂の軌跡、痕跡もしくは気配そのものであり、ついには作品あるいは「魂のメタファー」として、見る者の心を揺さぶることになるのだ。 リー・ユンボクの、ステンレスを屈曲した鏡面のように磨き上げた仕事はみな奇妙に人間的である。私たちがそこに私たちの魂が映し出されているように思うのはそのせいかもしれない。 |

| (多摩美術大学教授/府中市美術館長) |

| The Shape of the Soul ? Yunbok Lee’s Recent Works |

Kunio Motoe |

| The movie I am Legend starring Will Smith is a story about the last person in New York, which has been quarantined because of a plague. He is a doctor who has to fight off the former residents the plague turned into violent zombies, zombies that only come out at night. This alone is enough to call it a scary movie, but the part of this largely nonsensical movie that really sends shivers down your spine are not the action scenes. There is a scene in which on one quiet afternoon in a store void of people, our hero talks to an uncomfortably realistic mannequin, one that seems as though it could start talking at any moment, it is indescribably eerie. Faced with this scene, we are speechless and helpless, not understanding why being in the same space as something in the shape of a fellow human can stir up such an unsettled feeling within us. This is probably the first place we are confronted with the issue of the soul. Somewhere along the way I had the inappropriate thought that if a soul were to enter that empty shell of a finely crafted doll (I suddenly remember Pygmalion), she’d be a beautiful woman in the flesh. But what is this soul? Where is it? Nobody knows the answers to these questions. What we do know is that our souls are close to us, almost one with us, and like our faces or backs, they are not something we can look at directly. Souls do not reside in pieces of wood or stone. How can we catch something that appears unexpectedly with no way of knowing where it is? It is in this point that I for one, think the significance of Yunbok Lee’s work lies. Actually, this is not the first time I have seen the kind of shape in one of Yunbok Lee’s works that seems to have a soul. Several years ago, at the Soh Gallery, when I saw a certain work of art with organic form bound by a metal sash, I felt as if I sensed a soul locked inside. In contrast, more recent works give the impression the souls are independent, and much more self-sufficient. Yet, it is not the shiny, hammered and beat stainless steel encapsulating empty space itself that is the soul, that is just its shape. Moreover, we must not forget that the essential thing here is the idea Laozi expounds, namely that “Things in existence that are beneficial, are so only because of nothingness” (有之以爲利、無之以爲用). Incidentally, no matter how close the soul is to us, that does not mean it will show itself very readily. But that is exactly why Yunbok Lee says “Artworks are made on the border between the limits of mind and body. We go to sleep feeling the pain of the body, and so we awake.” And again, “…to me the process is a part of the artwork itself” (quoted from the artist’s notes). The soul always accompanies the dialogue and conflict of works that artists can refer to as pieces of themselves and at the same time entirely separate entities, affecting the materials as something almost non-existent. The accumulation and whole of these subtle events themselves, called “accidents” by the artist, are the tracks, traces, and signs of the soul. So that eventually the work of art, or “metaphor for the soul,” speaks to the hearts of those that look upon it. Yunbok Lee’s works of bent steel polished like a mirror are all strangely human. That may be the reason we think we see our souls reflected in them. |

Professor,

Tama Art University / Director, Fuchu Art Museum |

お問い合わせは gtsubaki@yb3.so-net.ne.jp